Kevin McLeod, GOV396, April 15, 2022

Introduction

In the spring of 1994 the Rwandan government, military services and extremist groups turned violently on a cultural minority. The ensuing massacre led to ~800,000 deaths in 100 days, ending in mid-summer. Estimates vary on the exact figure of lives lost, but the fact of genocide is not disputed.

The UN Tribunal – the “International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda” – was created by the UN Security Council to hold accountable and prosecute leaders and high-ranking supporters who enabled the genocide. It derives its authority from Chapter VII of the U.N. charter, which invokes universal jurisdiction for the pursuit of justice with regard to genocide. The tribunal is structured as a modified model of the earlier Yugoslavia tribunal.

The Tribunal

As planning for accountability commenced, it was considered critical to hold the tribunal as close to the center of events as possible, which meant around Kigali. Regional stability was still questionable when the tribunal was established in the fall of 1994, so the UN opted to host in plusher Arusha, Tanzania.

Air conditioning and greater security came with a trade-off; 18 hour drives to and from Kigali that circle south of Lake Victoria and Serengeti National Park. The roads were hazardous in patches, so it was an unpopular but mandatory trip. There was no rail. Air transport was prohibitively expensive and the UN wasn’t buying.

There were additional complications. In the time elapsed since the end of the genocide to the establishment of the tribunal, the Rwandan government had been toppled by RPF forces. That meant the court was dealing with a friendly government, which was good. But it was also a government still raw and unsettled, fresh from post-coup acquisition of power, where rule of law was still aspirational.

This was the context for the first international court of law in Africa to pursue justice for massive human rights violations. The court itself was physically split between Arusha in Tanzania, Kigali in Rwanda, The Hague in Holland, and the UN HQ in New York City. Which meant coordinating all details through distant nodes across different time zones, languages and cultures.

Combined with universally decried excessive bureaucracy at the UN, this made for a painfully slow and inefficient process. Insecure conditions created difficulties for insuring safety of witnesses, especially while Hutus remained the numerically dominant population.

Pre-genocide, there were more than 7 million people comprising 3 ethnic groups.

The Hutu (85% of the population)

The Tutsi (14%)

The Twa (1%)

Post-genocide, 70% of Rwanda’s Tutsi population had been wiped out, and many of the surviving 30% were very nervous. In Kibuye province, the figure was 90% – the 250,000 Tutsis living there had been reduced to 8,000. So providing security for witnesses was a serious problem.

The first prosecution was of Jean-Paul Akayesu, a town mayor who led massacres in his own city. His trial began in early January 1997 and ended with a guilty verdict on September 2 1998, a nearly two-year span. Today he’s doing life in an overcrowded prison in Benin, Africa. The tribunal would not close for business until the last day of 2016. Scott Straus, a published scholar who has examined the case closely, estimates active genocide participants numbered roughly 200,000, with most of the killing conducted by around 10% of that number.

Many of the most militant were aligned with MNRD, the president’s party.

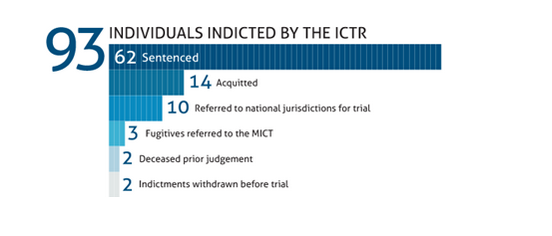

Of that roughly 20K core of genocidal militants, this infographic details how many were indicted and brought to some measure of legal accountability by the ICTR:

As of May 2020, six of the indicted have evaded arrest. A table of cases is available at https://ijrcenter.org/international-criminal-law/ictr/cas5e-summaries/

The full cost of the Rwanda tribunal amounts to ~US$1 billion. (Some sources claim double this) This works out to $10,752,688 per indictment, with 2/3 of those indicted sentenced for crimes. Incomplete evidence was a factor in many of the remaining third of indictments that became acquittals.

Context

Conflict and tension between Tutsi and Hutu peoples in Rwanda go back at least half a century and largely stem from colonial manipulation.

Rwanda was colonized for 77 years, between 1885 and 1962. For the first 34 years, it was ruled by Germans. Germany lost Rwanda and other colonies after WWI. Belgians took over in 1919 and remained rulers for 43 years, until 1962. In 1935, Belgium began including ethnic identity on passports.

Tutsis were regarded within Rwanda as an elite minority, the ruling class, and tended to be more economically secure. This made the Tutsi strategically attractive to colonizers, who favored them with a monopoly on power. Most of the population was Hutu, with a cohort of extremists blaming Tutsis for anything gone wrong. Resentment and peace came and went in waves. Some of the resentment was organic, in response to events, and some was manufactured at Radio Télévision Libre des Mille Collines, a government-affliated, Hutu-run station in Kigali. Since most people in the country had a radio and the station was broadly popular – it was the only national radio station at the time – extremists had a megaphone, major influence and government support.

A large new wave of rage directed at Tutsis crested when the president’s plane was shot down by surface to air missiles on return to Kigali airport. The president, Juvénal Habyarimana, was Hutu. Extremists immediately blamed the Tutsis, the Tutsi claimed it was a Hutu hit. To this day, much as in the US with JFK’s assassination, there is still no solid consensus on motive and whodunnit.

The incident became the flashpoint for a genocide that escalated quickly. The aggressors had practice; they had been conducting mass murder on a smaller scale in regional attacks, and many were veterans of fighting against RPF forces. Romeo Dallaire reports that several months before the genocide began, government officials were asking FAR forces to register all Tutsis in Kigali. This suggests plans for mass attacks were well underway before the president’s plane was shot down.

In her book Leave None to Tell The Story, Alison Des Forges’ thesis is that the genocide was organized and planned before it occurred. She was intimately familiar with Rwandan history, social dynamics and politics and her account was highly praised by Dallaire, who served in the field during the conflict. The Fate of Africa: A History of Fifty Years of Independence, Michael Meredith reports that the Defense Ministry chief Théoneste Bagosora imported 2x the normal annual purchase of machetes beginning in January 93 through March 94. A French investigation by Roland Tissot claims records argue against this, although the French have their own issues with their role in the genocide. The genocide began on April 6, the same day President Juvenal Habyarimana’s aircraft crashed and exploded.

This view has important implications for the Tribunal.

The dynamic conflict between the RPF, a Tutsi military force, and the Rwandan government (a Hutu force, FAR) was already escalating and had simmered at different temperatures for decades. The RPF had committed atrocities too, so many Hutu were receptive to accusations that Tutsis were responsible and eradication was desirable. Not all; moderate Hutus were also subjected to mass murder and other violence from their own communities. The divisions in Rwandan society were ideological as much as they were economic and and social. For the extremists in the FAR, being Hutu was not enough; one was either with the extremists and on board with their final solution for Tutsis or dead. They backed up that view with lethal force.

Cases

For most of its existence, the Tribunal was organized into three trial chambers in Arusha, Tanzania, an appeals chamber in the Netherlands at the Hague, and offices in Kigali, Rwanda. Judges were nominated by the Security Council and the UN General Assembly chose who would serve. Judges served four-year terms and were eligible to serve additional terms. The Tribunal began with 16 judges, which was supplemented in 2002 with 18 temporary ad litem judges who worked specific cases. At the outset, roughly half the judges were assigned to appeals, with the balance working trial cases.

While the ICTR did its work, Rwandan courts also processed cases. ICTR capped sentencing at life terms. Rwanda’s justice system allowed for capital punishment, leading to the public execution by firing squad of 22 convicted genocidaires in the spring of 1998.

Rwanda was deeply unsatisfied with the progress and quality of the Tribunal’s work, to the point that country dissociated from the Tribunal in 1999, but were persuaded to cooperate again in 2000. They were also unhappy that the trials had been moved out of the country to Arusha.

Rwanda’s dissatisfaction was widely shared. The International Center for Transitional Justice gave it this scorching review in a 2009 report:

“Since its creation, the Tribunal has been dogged by corruption, mismanagement and incompetence. The sluggish pace of genocide trials—just twenty-three completed trials (involving thirty-one accused) in ten and a half years—has been due to the absence of a clear prosecutorial strategy, poor case management and courtroom control by the judges and a largely incompetent administration.”

– Transitional Justice and DDR: The Case of Rwanda, Lars Waldorf, Research Unit, International Center for Transitional Justice, June 20096

The Tribunal had promised Rwanda outreach and education regarding the trials and results, but the promise wasn’t kept. Most Rwandans heard little about the trials and regarded the whole process as remote and ineffective.

One of the most important trials was that of Théoneste Bagosora, who was regarded as the de facto leader of the genocide after he assumed power following the death of the president. His personal diaries from 1992 include references to the formation of a ‘civil defense’ corp, a euphemism for a militant youth group closely affiliated with the Mouvement révolutionaire national pour le développement, (MRND). Soldiers from this group became the central, most active actors in the genocide two years later.

Bagosora was indicted on 12 charges. Two were dropped, 10 were upheld to conviction.

Count 2: Guilty of Genocide

Count 4: Guilty of Crimes Against Humanity (Murder)

Count 5: Guilty of Crimes Against Humanity (Murder of the Belgian Peacekeepers)

Count 6: Guilty of Crimes Against Humanity (Extermination)

Count 7: Guilty of Crimes Against Humanity (Rape)

Count 8: Guilty of Crimes Against Humanity (Persecution)

Count 9: Guilty of Crimes Against Humanity (Other Inhumane Acts)

Count 10: Guilty of Serious Violations of Article 3 Common to the Geneva Conventions and Additional Protocol II (Violence to Life)

Count 11: Guilty of Serious Violations of Article 3 Common to the Geneva Conventions and Additional Protocol II (Violence to Life of the Belgian Peacekeepers)

Count 12: Guilty of Serious Violations of Article 3 Common to the Geneva Conventions and Additional Protocol II (Outrages upon Personal Dignity)

Bagosora is the ‘devil’ Romeo Dallaire references in the title of his book about the genocide, Shake Hands with the Devil. Dallaire has said he struggled to gain some sense of closure over his experiences in Rwanda, and that seeing Bagosora in court wearing handcuffs during his 2004 testimony was the closest he’s come to it. The trial lasted five years and ended with a life sentence, which was later reduced to 35 years following an appeal. It remained a de facto life sentence; Bagosora died in prison at age 80.

The trial of Jean-Paul Akayesu – mayor of Taba, former school teacher – marked several milestones. It was the first trial held by the Tribunal, and his conviction was the first international court’s prosecution and guilty verdict on charges of genocide. It was also the first case to cite rape as an instrument of genocide. He was indicted on fifteen counts. Six counts were dismissed for insufficient evidence, conviction was found on 9:

Count 1: Guilty of Genocide

Count 3: Guilty of Crime against Humanity (Extermination)

Count 4: Guilty of Direct and Public Incitement to Commit Genocide

Count 5: Guilty of Crime against Humanity (Murder of three Tutsi civilians)

Count 7: Guilty of Crime against Humanity (Murder of 8 Tutsi refugees)

Count 9: Guilty of Crime against Humanity (Murder of five civilian Tutsi teachers)

Count 11: Guilty of Crime against Humanity (Torture)

Count 13: Guilty of Crime against Humanity (Rape)

Count 14: Guilty of Crime against Humanity (Other Inhumane Acts)

His appeal was dismissed by the court, and he is currently serving a life sentence in Benin, Africa.

The trial of Ferdinand Nahimana, propagandist and RTLM head, was often referred to as the Media Case, because he and two others were prosecuted for their contribution to genocide via malicious, inflammatory encouragement to kill by radio broadcasts throughout Rwanda.

Criticism

As mentioned in the introduction to the Cases section, there is a great deal of deep dissatisfaction with the Tribunals’ pace of work and volume of convictions. At the outset, the Tribunal aimed to prosecute the leaders of the genocide and leave most cases related to lower-level militants to the national and gacaca (“grass”) courts. While the quality of justice in local courts is uneven, the resort to community courts was necessary due to the number of trials. The UN reports that 12,000 gacaca courts tried 1.2 million cases involving ~130,000 militants. The Tribunal simply didn’t have the resources needed to process so many cases.

That said, the Tribunal did have very substantial resources, amounting to at least a billion dollars over time it remained active before shutting down in 2016. Despite this, the Tribunal was notorious for extremely slow pacing, issues with coordination and the need to add 18 ad litem judges.

Another major concern is the lack of RPF prosecutions. In the process of prosecuting a war against the Rwandan government, the RPF committed atrocities and sent children to fight.

Abdul Ruzibiza, a former RPF lieutnant in Network Commando unit working for the Department of Military Intelligence (DMI), testified that “…wholesale extermination of Hutu populations in places like Kageyo, Meshero, Mukarange, the regions of Gokoro and Kabuga, the commune of Bicumbi where “at least 3,000 persons were killed” under the supervision of the High Command Unit, [Paul] Kagame’s personal guard, at the request of Kagame himself.”7

The Gersony Report adds that “during the months from April to August the RPF had killed between 25,000 and 45,000 persons, between 5,000 and 10,000 persons each month from April through July and 5,000 for the month of August”.

https://www.hrw.org/legacy/reports/1999/rwanda/Geno15-8-03.htm

Because of this, many decried the end result ‘victor’s justice’, indicating a biased process that left real RFP crimes unprosecuted because the RFP defeated the Rwandan government. This extends beyond the post-genocide war and well into the establishment of governance by the RPF. By 2001, the U.S Department of State has observed that “…the government’s human rights record in 2000 remained poor and that it “continued to be responsible for numerous, serious abuses…the Army was accused of extra-judicial killings.”8

Conclusion

Ultimately the principal perpetrators were brought before the tribunal and sufficient evidence for Western standards of guilt made many convictions and severe sentences possible. There are still disquieting reminders of the genocide. In Kibuye, by 2004 the number of Tutsi in the areas has fallen from 8,000 to 1,000, and those who remain are outnumbered by people who directly participated in the genocide. This reality contributed to the steady decline of Tutsi in the area – they left for safer areas.

In the animal kingdom, we frequently see flocking behavior. Fish do it, birds do it, mammal herds do it. People are not that different. They’re watching leaders and the people around them, trying to figure out what direction their tribe will take. Most will follow the path of least resistance, taking someone else’s judgment over their own. Thus we get flocks of people in thrall to a few charismatic leaders. When those leaders urge them to hate and kill, people will flock in that direction.

This is what happened in 1930s and 1040s Germany, it’s what happened in the Jim Jones mass suicide incident, and it’s what happened in Rwanda. Flocks can travel towards healthy goals or toxic, hellish traps laid out by their own leadership.

We have already seen the American Republican party do this. If their leadership is able to regain power, the potential for genocide in the USA will be real, and could occur with rapid speed. Never assume it can’t happen here. It can. If it does, the UN now has tribunal management experience and will perhaps improve the next time around.

Book Sources:

Shake Hands with the Devil by Romeo Dallaire

We Wish to Inform You That Tomorrow We Will Be Killed With Our Families by Philip Gourevitch

The Fate of Africa: A History of Fifty Years of Independence by Meredith, Martin. (2005)

Leave None to Tell the Story: Genocide in Rwanda by Alison Des Forges

https://www.hrw.org/reports/1999/rwanda/index.htm

Journal sources

Transitional Justice and DDR: The Case of Rwanda by Lars Waldorf

https://www.ictj.org/sites/default/files/ICTJ-DDR-Rwanda-CaseStudy-2009-English.pdf

Rwanda: the state of Research by Lemarchand René

https://www.sciencespo.fr/mass-violence-war-massacre-resistance/en/document/rwanda-state-research

Interview with Philip Gourevitch

https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/1844138

Propaganda vs. Education:

A Case Study of Hate Radio in Rwanda

David Yanagizawa-Drott, Harvard University

Online Sources

Meaning of Hutu, Tutsi and Twa

https://www.hrw.org/reports/1999/rwanda/Geno1-3-09.htm

Gersony Report

https://www.hrw.org/legacy/reports/1999/rwanda/Geno15-8-03.htm

Rwanda Radio Transcripts from Montreal Institute for Genocide and

Human Rights Studies

https://www.concordia.ca/research/migs/resources/rwanda-radio-transcripts.html

Video confessions

https://genocidearchiverwanda.org.rw/index.php?title=Category:Perpetrator_Confessions

ICTR criticism

https://www.dw.com/en/ictr-a-tribunal-that-failed-rwandan-genocide-victims-and-survivors/a-51156220

Rwanda: Tribunal Risks Supporting ‘Victor’s Justice’

https://www.hrw.org/news/2009/06/01/rwanda-tribunal-risks-supporting-victors-justice

Rwanda 10 years on

https://www.theage.com.au/world/rwanda-10-years-on-not-forgiven-not-forgotten-20040403-gdxm3l.html

Rwanda 20 years on

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2013/may/12/rwanda-genocide-20-years-on

‘Music to kill to’: Rwandan genocide survivors remember RTLM

https://www.aljazeera.com/features/2020/6/7/music-to-kill-to-rwandan-genocide-survivors-remember-rtlm