Kevin McLeod, Gov 391, 2021

In 1969, Canadian prime minister Pierre Trudeau spoke at the Washington National Press Club, where he memorably described the relative scale of relations between Canada and the U.S.:

“Living next to you is in some ways like sleeping with an elephant. No matter how friendly and even-tempered is the beast, if I can call it that, one is affected by every twitch and grunt.”

The analogy still applies. In territorial terms, Canada is vast. In population, less so – the current count is just over 38 million. U.S. population is approaching 334 million, nearly 10x larger. Most of Canada’s population, 85%, lives in its south, within 120 miles of its border with America. In broad swaths of Canadian land, people are outnumbered by bear and moose. This difference in population is one of the most influential factors in relations between the countries.

Economics

Despite the population disparity, the balance of trade between the two countries favors Canada. In August 2021, exports to Canada were valued at $25.73 billion, whereas imports from Canada were valued at $31.69 billion – a $5.33 billion US trade deficit.

At the household level, Canadian indebtedness as measured by the debt-to-disposable-income ratio reached 175% in 2020, compared to 105% in the United States. This measure can be good or bad, depending on the viewpoint. A higher ratio indicates a greater degree of wealth, and in this Canada is in good company, placing it among the top 10 wealthy northern European nations. Creditors are reluctant to lend to households with insufficient wealth, so by this measure Canada is a low-risk debtor. On the other hand, of course, it means a larger level of debt, and therefore more vulnerability to economic downturns.

Risk is low as long as economic growth remains strong, but rises sharply when it weakens. Creditors evidently assess the risk of lending to Canadians to be low. The U.S., in contrast, has a lower ratio, which suggests much of the population there is a greater risk. Pre-pandemic reports find that nearly 40% of Americans would struggle to deal with a emergency $400 expense. Post-pandemic figures may show greater stress.

This affects trade relations because Canada and the U.S. are each other’s best foreign markets. While household Canadian wealth remains stable, U.S. wealth is contracting. The reasons for this are complex – the picture in both countries is distorted by wealth inequality, particularly in disparities between homeowners and renters as financial engineering drives up home values. Home ownership in the U.S. as of Q3 2021 stands at 65.4%. Among Canadians the figure is 68.55%.

The U.S. Office of the United States Trade Representative (USTR) finds that in 2019, U.S. foreign direct investment in Canada, primarily in stocks, was $402.3 billion, while Canadian foreign direct investment in the United States was $495.7 billion. As is evident from current events, political instability is a growing risk in the U.S. This could expand the gap between the two countries as investors seek safe havens.

The Journal Of Commerce notes that export trade in goods and services with the U.S. in 2019 (a year often cited as a pre-covid benchmark) made up nearly 1/3 of Canada’s entire GDP. American business with Canada comprised 12% of U.S. GDP – a sizable amount, but one that makes relative dependency clear.

This reality is made more vivid by a singular fact: Canada’s trade balance in goods with the U.S. is now the best it’s been since 2008. But thirteen years on, it still hasn’t returned to the levels it was at prior to the Great Recession. A common truism about the close linkage in economic relations with the U.S. notes that when the American economy catches a cold, Canada gets the flu.

As of 2021, we can confidently say economic relations are robust and likely to remain so, despite areas of disagreement. Biden’s cancellation of the Keystone XL pipeline project was a major economic disappointment for Canada but an environmental win. And this is where we pivot from economics to environment, as there is a close linkage here too.

Environment

Canada is faced with an awkward and growing dilemma in that the largest portion of value in exports to the U.S. – euphemistically referenced as “mineral fuels” by the USTR – is fossil fuel in the form of tar sands extracted in Alberta.

Crude, heavy oil is refined from bitumen mixed in the sand, a process that is both more energy-intensive than straight extraction from oil deposits and results in a product that generates more pollution than lighter oil. This low grade fuel is commonly used to power large container shipping vessels. As climate change prods the world to move toward renewables and nuclear energy, the value of tar sands falls. Replacing this level of value in the Canadian economy will not be easy, but the current administration at least acknowledges the challenge.

One potential source for new income is more mining, an industry where Canada is adept. About 50% of the active mining firms worldwide are Canadian. Opportunity knocks in the form of growing demand for minerals like nickel and cobalt that are required for electric vehicle production. Proven reserves of minerals most in demand are minimal, especially in comparison to China, but surveys are underway to explore areas that may contain additional sources. However, industrial-scale battery chemistry and production processes are a moving target as battery technology is refined, so today’s hot mineral commodities may be discarded in favor of others later. This complicates planning.

Although somewhat speculative at this early date, global expertise in the full spectrum of mining conditions may prove valuable in the years ahead as extraction of lunar and asteroidal minerals become more relevant. The mantra of lunar settlement is in-situ resource development, and Canadian firms are well-positioned to be a key player in that field. Although somewhat speculative at this early date, global expertise in the full spectrum of mining conditions may prove valuable in the years ahead as extraction of lunar and asteroidal minerals become more relevant. The mantra of lunar settlement is in-situ resource development, and Canadian firms are well-positioned to be a key player in that field.

Canada’s per-capita energy consumption is among the highest in the world, partly due to geographical location. Heating homes, factories, businesses and schools consumes a lot of energy during Canada’s long winters.

Canada is clearly feeling the effects of climate change. Only a few weeks ago, severe flooding in south British Columbia temporarily cut off Vancouver from the rest of Canada through the loss of roads – it became necessary to drive south into the U.S. and back up to Canada to get around washed out highways. Past years have seen severe fires in northern Alberta, and the range of areas vulnerable to fire will expand. Melting ice in the Arctic regions north of Canada is opening up new shipping channels, already a source of tension with Russia.

Canada’s future will see hazards borne by melting ice, fire and water, with growing price tags attached to each. Global warming may open up more areas to farming and expand the selection of farm products, but will also upend existing ecosystems, creating favorable conditions for invasive species and diseases affecting crops, wildlife and people.

Security & Institutions

Our course textbook examines international relations with reference to the realist, liberal, Marxist and constructivist models. In Canada-US Relations: Sovereignty or Shared Institutions, authors David Carment and Christopher Sands of Canada’s Royal Military College offer a clear-eyed alternative model they call the 4-I framework. It builds on previous work by Griffith, Hamm (2006) and Schmidt (2008, 2010, 2011, 2017). This theory focuses on four key variables; institutions, interests, ideas and identity.

They emphasize that these variables are not and cannot be analyzed in isolation; each one interacts with all the others. As they put it, “Political ideas, for example, cannot be analyzed in isolation from interests, institutions and identity.”

Stated plainly, this seems self-apparent and obvious at first glance. But the tendency to simplify analysis by isolating variables, or even treating them as static values rather than variables, is strong and warrants resistance, so this is a welcome observation. A holistic view is more complex, but in competent application also capable of generating more realistic results.

The institutional aspects of mutual security measures have increased in scope, depth and intensity for several decades, spiking in the wake of 9/11. Integration between security agencies has expanded to include embedded officials working in each other’s agencies on land and at sea. This has the effect of fostering informal networks, bolstering cultural understanding, establishing greater levels of trust, and enabling new programs like fusion centers where Canadian and American security personnel physically work together.

Under the umbrella of the Canada–US Cross-Border Crime forum (CBCf), the specific institutions working together include…

Public Safety Canada

Canadian Department of Justice

Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP)

Public Prosecution Service of Canada

U.S. agencies include…

Department of Homeland Security

U.S. Department of Justice

U.S. Attorney’s Office

Federal Bureau of Investigation

Drug Enforcement Administration

US Coast Guard

Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco & Fireworks

Immigration and Customs Enforcement

These efforts focus on policing, border and coastal security, ports of entry and counter-terrorism. This has elevated awareness to the point of comprehensive real-time surveillance of traffic between nations together with free and full exchange of data.

The U.S. response to 9/11 was firmly within the realist model, which exercised power to deliver a message to the Muslim world; destroy what is ours, we will visit 10x more destruction upon what is yours. The strategy proved ineffective. Afghanistan remained controlled but unconquered after 20 years of war. Iraq, subjected to a pre-emptive war that set off a horrific internal civil war, also proved itself ungovernable by Western systems. Force was able to shatter the ISIS movement that emerged in response, but largely because most Muslims themselves rejected the movement.

Canada has contributed troops to NATO, the UN and the US for a variety of military missions, but refused to participate in the invasion of Iraq. It was, then and in retrospect, a wise choice. Canada’s foreign policy and interests are necessarily closely tied to the U.S., but not identical. It exhibits more of the liberal tradition, seeking cooperation where possible and using diplomacy to mitigate conflict. It’s true that Canada’s limited native military capabilities make this a matter of necessity as much as a policy. Living in the shadow of the much larger U.S. military comes with both benefits and drawbacks. Greater domestic security is the obvious benefit. Lesser independence in decision-making is the drawback, although the U.S. has accepted differences in this.

The inherent tension of cooperation and conflict is playing out now as Canada considers how to update its fighter jet fleet. It currently fields CF-18 Hornets built in the 80s, supplied and serviced by Boeing. Canada entertained bids from Boeing for updated F/A Super Hornets, from Lockheed Martin for their F-35, and Swedish manufacturer Saab’s JAS-39 Gripen.

Two other European firms considered competing but dropped out after concluding that the specifications essentially required interoperability with American and allied aircraft, which they could not deliver. If so, this probably means the Saab bid is also destined for rejection. Canada already dismissed Boeing’s Super Hornet bid, likely in reaction to Boeing’s lawsuit against domestic aircraft manufacturer Bombardier, leaving the F-35 as the most likely contender.

This comes with a major problem, however – the price tag. The F-35, as an advanced “5th generation” aircraft, comes with a very hefty purchase price – $80 to 110 million each – and maintenance costs, more than Canada can reasonably afford. Unless the U.S. agrees to subsidize Canada’s F-35 purchases and operating costs, Canada’s only real choice may be to fall back on Boeing for Super Hornets. As of this writing, they have purchased 25 used Hornets from Australia to keep the existing fleet active.

These considerations illustrate the dilemmas faced by a smaller American ally expected to support North American security.

Immigration and Mutual Interests

U.S. and Canadian security interests are closely aligned, not only due to shared geographic space, but also cultural space – the values of civil rights, commitment to democracy, opposition to authoritarian governance, and support for free and fair trade. Immigration, a topic mired in controversy during Trump’s time in office, is challenging for Canada in that they do not have the American scale of resources to deal with it.

Canada’s annual immigration normally amounts to around 300,000 people, which is one of the world’s highest rates per population. 11 Fully 21% of the population are immigrant permanent residents. This planned level of immigration is manageable, but when an unexpected surge of immigrants from America peaked at a rate of 8,000 per quarter during the Trump administration – about 10% of the planned level – this was enough to stress Canada’s immigration system.

For comparison, legal U.S. immigration in 2019 totaled 1,031,765 new permanent residents, roughly consistent with the previous 14 years. However – and readers can be forgiven for thinking otherwise, given the drama on the topic over the past six years – U.S. immigration rates have actually been decreasing every single year since 1999. Sometimes sharply, sometimes only slightly, but every year sees a decrease. This has played a role in labor shortages around the U.S., together with more limited movement of people due to the pandemic. While Canadian immigration rates continue to grow, U.S. rates are languishing.12 13This has myriad impacts on relations between the two nations.

Canada’s lower population and substantial economic resources make immigrant labor an attractive proposition. It powers further growth, helps secure a robust social safety net, and adds diversity to communities.

Canada’s embrace of immigration and diversity differs from about 1/3 of the U.S. population’s view on the matter and broadly agrees with the other 2/3s. This creates tension during periods of conservative political influence in the U.S. while inviting cooperation in policy and practice during more liberal U.S. administrations. This pattern of alignment and divergence works in reverse as well, when the conservative Harper administration maintained a formal and somewhat frosty relationship with the Obama administration.

There is considerable difference between conservative governance in Canada and conservative governance in the U.S. For example, Canadian conservatives seldom challenge the validity of social service policies because they are popular in Canada, whereas U.S. conservatives routinely do. These differences reflect distinct histories and attitudes. Canada doesn’t have a sizable culture that believes “government is the problem”.

Canada’s agricultural sector has never been dependent on slave labor and consequently never developed the harsh culture of exploitation and hierarchy that still permeates the rural American South. Also in contrast to the U.S., Canada didn’t revolt against English rule. This resulted in different national narratives. The imprint of those forks in development centuries ago still influence attitudes today.

Health Care

Americans get their health care coverage from four broad sources; private insurance through employers, government-funded Medicare for the elderly, government-funded Medicaid for low-income citizens, and emergency room care funded from a variety of sources. As of 2020, 30 million people have no health insurance. This is an improvement. Prior to the passage of the Affordable Health Care Care, aka “Obamacare” the total was 48 million. “The uninsured are disproportionately likely to be Black or Latino; be young adults; have low incomes; or live in states that have not expanded Medicaid.” (i.e., “red states”)

Canadians have universal health care coverage for all citizens, funded by federal subsidies. By OECD standards, Canada is regarded as relatively generous among developed nations in spending 11.5% of GDP on health care in 2019. By contrast, U.S. health care spending amounts to 18% of GDP in 2020.

Why is America paying more? Since 1999, the percentage of administrative expenses in both nations has remained remarkably stable. In Canada it is 16%. In the U.S. it is 31%. In 2020 U.S. dollar terms, this translates to $2,500 per person in the U.S., $550 in Canada.14 None of this funding goes to actual care. Canada’s universal health care system spends half as much on administrative costs, 37% less overall than the U.S. does, and is still able to provide universal coverage.15

In addition, Canadian physicians have access to publicly subsidized medical school training, malpractice protection provided covered by the government, lower administrative costs and lower financial risks than U.S. doctors.

Foreign Policy & National Identity

An ongoing theme in Canada’s national discussion about the U.S. is apprehension about cultural, economic and political dominance. The debate isn’t over whether the U.S. dominates these spheres; it’s more about how much.

Some of this concern has been alleviated by the experience with Donald Trump. While Canada made some concessions to U.S. demands in the face of significant pressure, particularly around the issue of the North American Free Trade Agreement, it refused to concede on other matters, most notably on coronavirus management. As Trump attempted to minimize a growing pandemic, Canada responded by closing its border to American citizens.

In an effort to bolster Canadian culture, music broadcasters are required by law to devote 35% of airtime to domestically sourced programming. Similar quotas were once imposed for television and film, but as the internet has blurred the meaning of domestic production – and American filmmakers have increasingly used Canada as a lower-cost alternative to filming in union-strong Hollywood – the emphasis has shifted towards subsidies for Canada-centric content.

Democracy and the Debate of Ideas

The role of the state in national affairs is one of the key areas where Americans and Canadians markedly differ. Regulatory capture is certainly a part of Canadian governance, so corruption is at least common in both countries, albeit masked as legitimate practice. But support for regulatory restraint in business is far stronger in Canada. This goes back, again, to differing national experiences.

Saskatchewan trialed universal healthcare in the early 60s, and from there it spread to become a national program. The U.S. has never offered universal health care and debate over the concept remains stymied by legal bribery, aka “lobbying” and public/private obstruction. A survey conducted in 2004 found Canadians are ambivalent about military service, with 60% considering it a citizen’s duty, whereas Americans are somewhat more gung-ho at 75%. The same survey found 91% of Canadians believe understanding others is an essential value for engaged citizens. Americans came in at 85%.

In other aspects of the survey, both countries are generally within 3-4% of each other on values, small enough to be within a margin of error. There is a great deal of overlap in the value sets of Canadians and Americans.

Much of the similarities in values can be ascribed to overwhelming American cultural influence; generations have grown up watching American television, listening to American music, reading American news sources, magazines and books.

As American millennials shift away from legacy broadcast media to the internet, values are shifting as well. They have adopted a value set that looks closer to Canadian values than boomer American values. Support for progressive concepts like universal health care, a stronger social safety net, increased mass transportation, acceptance of diversity and recognition of climate change all mirror similar views among the full age spectrum in Canada.

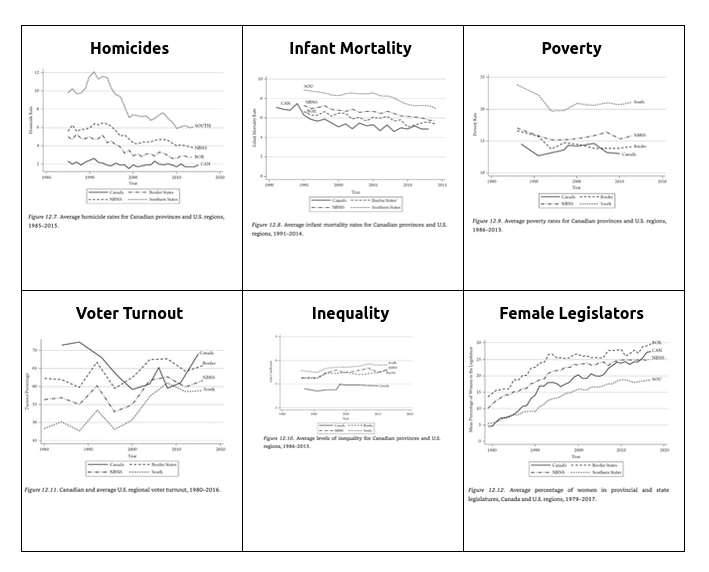

In “The United States and Canada: How Two Democracies Differ and Why It Matters”, chapter 12 examines six specific metrics – homicide rates, infant mortality, poverty, inequality, voter turnout and gender inequality among legislators – and compared the Canadian numbers with three distinct U.S. regions. They are grouped as the northern border states (labeled BOR in the following graphs) the South, and the rest of the states, (non-border, non-south, labeled NBNS).

The results are striking. By nearly every measure, the 11 states along the Canadian border – Alaska, Washington, Idaho, Montana, North Dakota, Minnesota, Michigan, New York, Vermont, New Hampshire and Maine – are closer to Canadian values than their Southern and non-border, non-southern counterparts. The one exception is U.S. border states have more female legislators than Canada.

What drives this similarity in outcomes between the northern border states and Canada? The authors examine a variety of possible factors, including proximity, shared cultural values, institutions, governance and population diversity. For various reasons, none of these alone or combined produce fully satisfying answers, as they are contradicted by other factors that should be applicable but are not.

The one common denominator, an obvious one, is climate. We already know that different climatic environments often produce distinct cultures. Within the U.S., we see this in the north/south axis. There is north/south cultural divergence in Europe as well, manifesting in different ways. In both the U.S. and Canada, we see it in the east/west axis, with clearly different cultures on the west and east coasts.

While it seems like a simplistic explanation, perhaps we shouldn’t be surprised. As humanity has migrated across the planet from its African origins, populations have settled in various environments and climates and adapted, mind and body, to that climate. The African hunter is distinctive from the Inuit. Both are distinct from settlers who populate the Asian steppe. None of them could live in ease at the high altitudes – nearly 17,000 ft – occupied by some Peruvians.

Humans are, in a sense, environmental specialists. We can reasonably infer that adaption affects temperament as well. While the ease of movement in modern times dilutes this effect to some degree, the persistence of place conserves cultures and the people who live in them. Living in the cold end of a temperate zone, as northern Americans and Canadians do, may well foster similar temperaments, problem-solving approaches and values. If climate is in fact a major influence on shared values, climate change takes on an entirely new dimension.

On the east coast, one famous phenomenon is the annual migration of “snowbirds” between Ontario and Florida. Each year, tens of thousands of Canadians come to Florida to winter, then flock back to Ontario as it warms. They have adapted to moving between climates and cultures. We might do well to study how it works for them, as we enter a world where climate change will compel human migration on a scale never seen in modern times. A popular Canadian slogan declares, “The world needs more Canada”. In the decades ahead, many Americans may come to agree.

Bibliography

Texts

The United States and Canada: How Two Democracies Differ and Why It Matters

2019, Paul Quirk, 1st Edition

Canada–US Relations: Sovereignty or Shared Institutions? (Canada and International Affairs)

2019, David Carment & Christopher Sands, 1st Edition

Congressional Research Service

Canada-US Relations. (2018). https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/RL/96-397/48

Additional economic data:

Canada-US Relations. (2021). https://www.everycrsreport.com/reports/96-397.htm

Journals

Canadian Journal of Political Science

https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/canadian-journal-of-political-science-revue-canadienne-de-science-politique

International Journal: Canada’s Journal of Global Policy Analysis

https://journals.sagepub.com/home/ijx