Kevin McLeod, GOV 348, 4/7/22

I agree with Senator Finistirre.

For starters, equating cigarettes with generic poisons is a false equivalence. Cigarettes have some unique properties.

The dose makes the poison. How much a person smokes greatly influences their level of risk. Secondly, there’s the addictive nature of nicotine. People vary greatly in their ability to manage addiction. There are of course addictions that are not poisonous (gambling) and poisons that are not addictive (Fox News, Little Debbie pastries, WWE wrestling…) Even water can become a poison in excessive amounts, but no one proposes we add poison labels to bottled water.

Cigarettes warrant poison labels because they are proven carcinogens and addictive by design, making it difficult for people who recognize their risks to quit. It’s a “sticky” poison, highly profitable for vendors because the social costs are externalized – higher medical expenses, money wasted feeding the addiction, shortened lives, second-hand smoke. Cigarettes have also long been marketed to youth with the aim of creating a lifetime customer.

This is the primary audience for a poison label, as an early warning. We can’t always rely on parents to convey this warning because they themselves may be addicted to cigarettes, and thereby modeling the role of a smoker and normalizing that behavior.

In short, cigarettes present a heightened risk of health problems, debt, and death. Calls for “consumer freedom” are often a mask for predatory marketers. Poison labels for cigarettes is already a routine practice in Europe, and the U.S. can learn from that example.

Question Two

Yes, Nick’s claim is morally and politically dubious. It’s a rationalization. First of all, let’s acknowledge that cigarettes are marketed for a singular purpose – to earn a profit. These profits come at the cost of people’s health, lifespan and significant personal expense. It is a clear harm marketed as a lifestyle.

The common rebuttal to this point of view is that people should be entitled to pick their own poison, to commit slow suicide if they wish. After all, prohibition was tried with alcohol and drinkers successfully fought and undermined that effort.

This would be a reasonable argument if nicotine addiction didn’t bypass personal willpower and hijack health by creating unrelenting cravings. Addiction undermines rational decision-making ability, and industry resistance to mandated lower nicotine levels exposes its agenda – they know keeping customers hooked is the key to maintaining high profits. Knowingly selling an ultimately deadly product and pretending that’s acceptable is morally indefensible.

Politically, state and local governments that collect considerable revenues from cigarette taxes are incentivized to take a lax view of regulation. In some states, taxes alone account for more of the cost than the product itself.

Higher prices have helped reduce smoking, so higher taxes have also been a backdoor form of health regulation. When Joe Sixpack can no longer afford a pack-a-day habit, it’s a powerful incentive to give it up.

Nick has a talent, surely. But he has a range of choices in how to exercise it, and he choose to go with the highest bidder. His choice continues a vicious cycle; he supports an exploitive, high-revenue industry that can afford to pay him well because he aids the exploitation. Sure, if Nick quits someone else will replace him, and that person may be more, less or equally effective as Nick.

But Nick has made a choice, even if he doesn’t acknowledge it. He’ll shake hands with devils in nice suits and not look too closely at the tragic consequences. In the film, he’s comfortable with his job until he’s confronted with the question – what would you tell your kids about these products? He knows he lies for a living. But his capacity for self-deception is at least as strong as his talent.

Question Three

The portrayal is accurate in that it demonstrates some common deceptive tactics. Take his analogy of poison labels. The currently fashionable term for that tactic is “whataboutism” – making a false equivalence to distract from issues related to the products he defends. Another is offering accurate but cherry-picked, incomplete information that leaves out critical context, perspective and facts that provide more complete understanding. Another tactic is minimization – scoffing and depreciating both a message and a messenger as irrelevant, confused or ignorant. Feigned skepticism is an effective way to pose as a defender of truth.

These and other tactics, deployed in a low-key manner, can be very persuasive with people who are unfamiliar or overly trusting. This toolbox of manipulation isn’t limited to lobbyists – it will be found anywhere there is something of value and people skilled at jiving their way to preferential access, where the risks of deception are lower than reward.

The portrayal is inaccurate in that it doesn’t convey what proportion of lobbyists actually work this way. As our textbook and guest speaker Zainab Alkebsi have pointed out, the lobbying profession can function ethically and often does. Many lobbyists are essentially serving as negotiators, seeking accommodation among various interests that change over time. Where values are not high stakes, or the issues are non-commercial, deceptive tactics aren’t needed and can become a liability. This film focuses on a mercenary commercial lobbyist, and isn’t representative of lobbyists in all fields.

Question Four

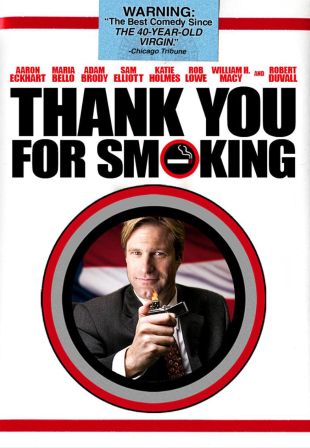

Thank You For Smoking is a parody of lobbyist behavior, an exaggerated cartoon portrayal. The take-home for viewers is the exposure of deceptive strategies and glib sound bites that can sway audiences. These are real, but by presenting them in an exaggerated form, more people are able to see them clearly as marketing rather than truth.

It also demonstrates the uneasy relationship between marketing and truth. Accurate facts can be presented in slanted ways, and commercial interests routinely edit for the best possible slant. The most favorable and positive angles are emphasized, downsides are neglected or ignored. Insurance companies never run ads about what they don’t cover. We live in a society that takes this practice for granted. Many people do the same thing with their resumes. This is buyer-beware culture.

Because that culture permeates our society, it touches lobbying as well. We can’t ban lobbying or lobbyists. Government, business, NGOs, labor, any group, they all have some legit issues that need resolution. Lobbyists serve as problem-solving communicators representing various interests. The best we can do is establish ethics standards, hold lobbyists to them, and have systems able to recognize serious ethical problems early and intervene before they metastasize.